Data Platforms and Artificial Intelligence

Challenges and Applications

DISI — University of Bologna

m.francia@unibo.it

Metadata Challenges

Lacking smart support to govern the complexity of data and transformations

Data transformations must be governed to prevent DP turning into a swamp

- Amplified in data science, with data scientists prevailing data architects

- Leverage descriptive metadata and maintenance to keep control over data

Metadata Challenges

Knowledge representation

- Which metadata must be captured

- How should metadata be organized

Knowledge exploitation

- Which features do metadata enable

Which metadata must be captured?

Which metadata must be captured?

A classification of metadata (Sharma and Thusoo 2016)

Technical metadata

- Capture the form and structure of each dataset

- E.g.: type of data (text, JSON, Avro); structure of the data (the fields and their types)

Operational metadata

- Capture lineage, quality, profile, and provenance of the data

- E.g.: source and target locations of data, size, number of records, and lineage

Business metadata

- Captures what it all means to the user

- E.g.: business names, descriptions, tags, quality, and masking rules for privacy

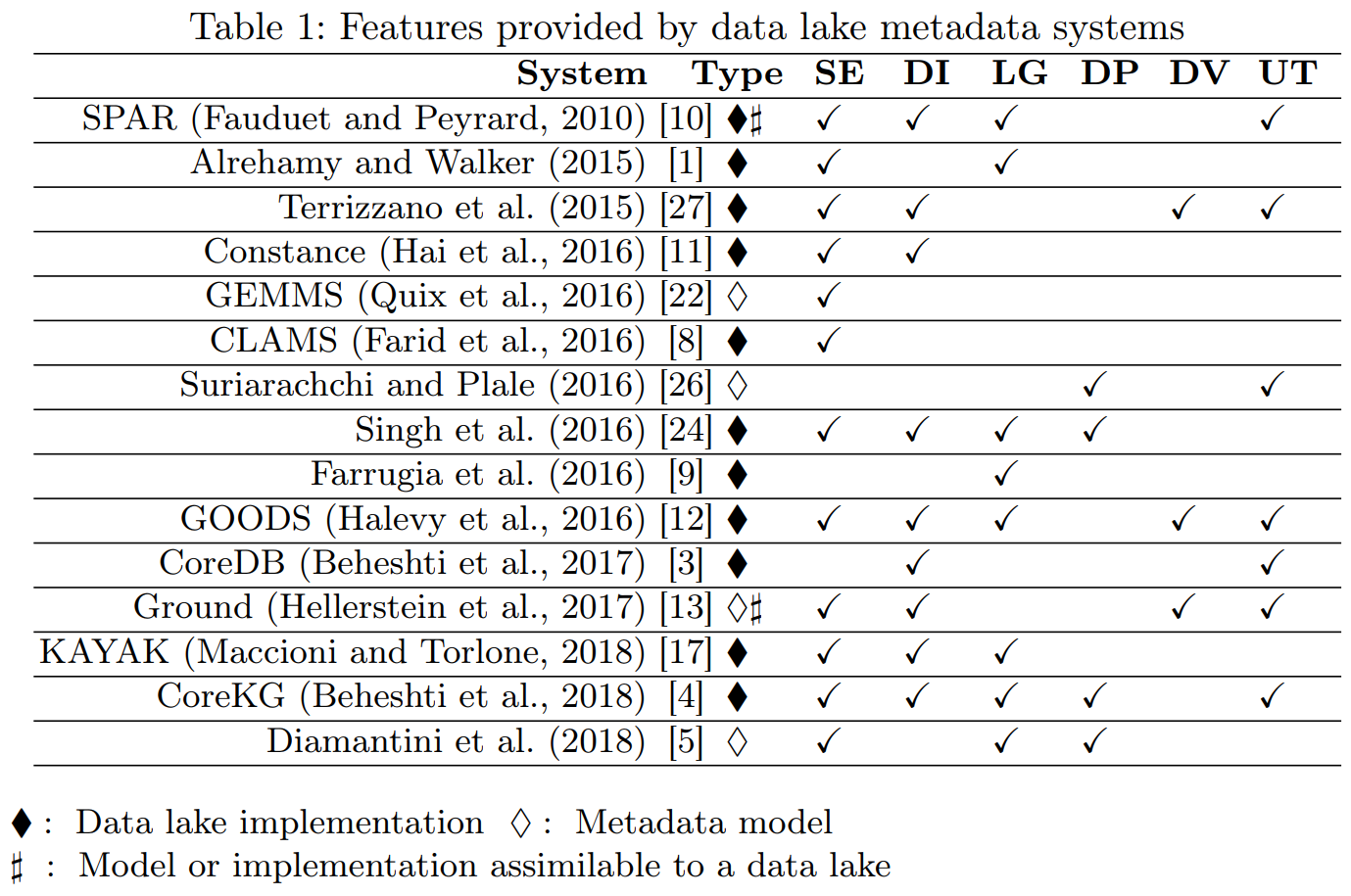

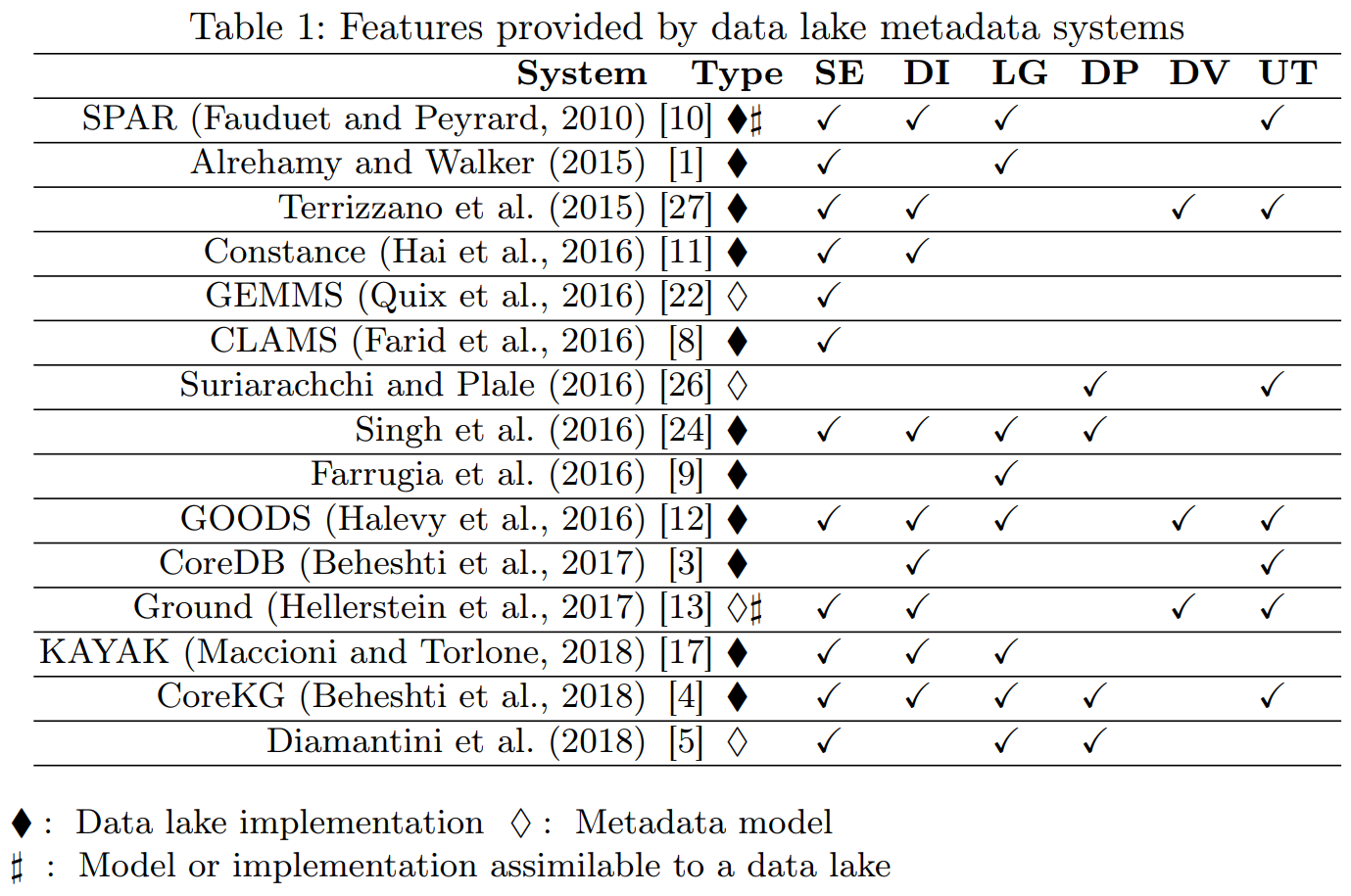

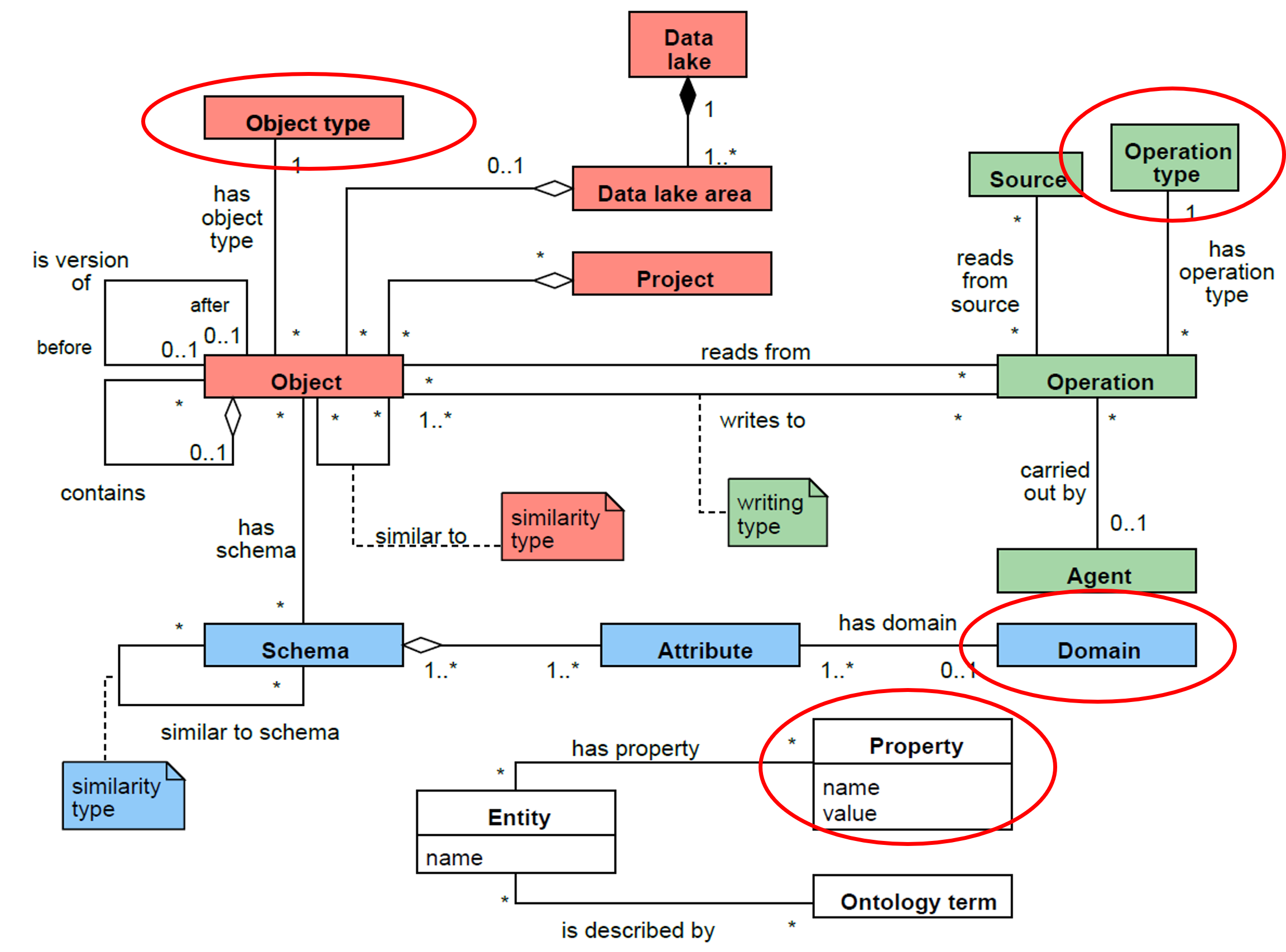

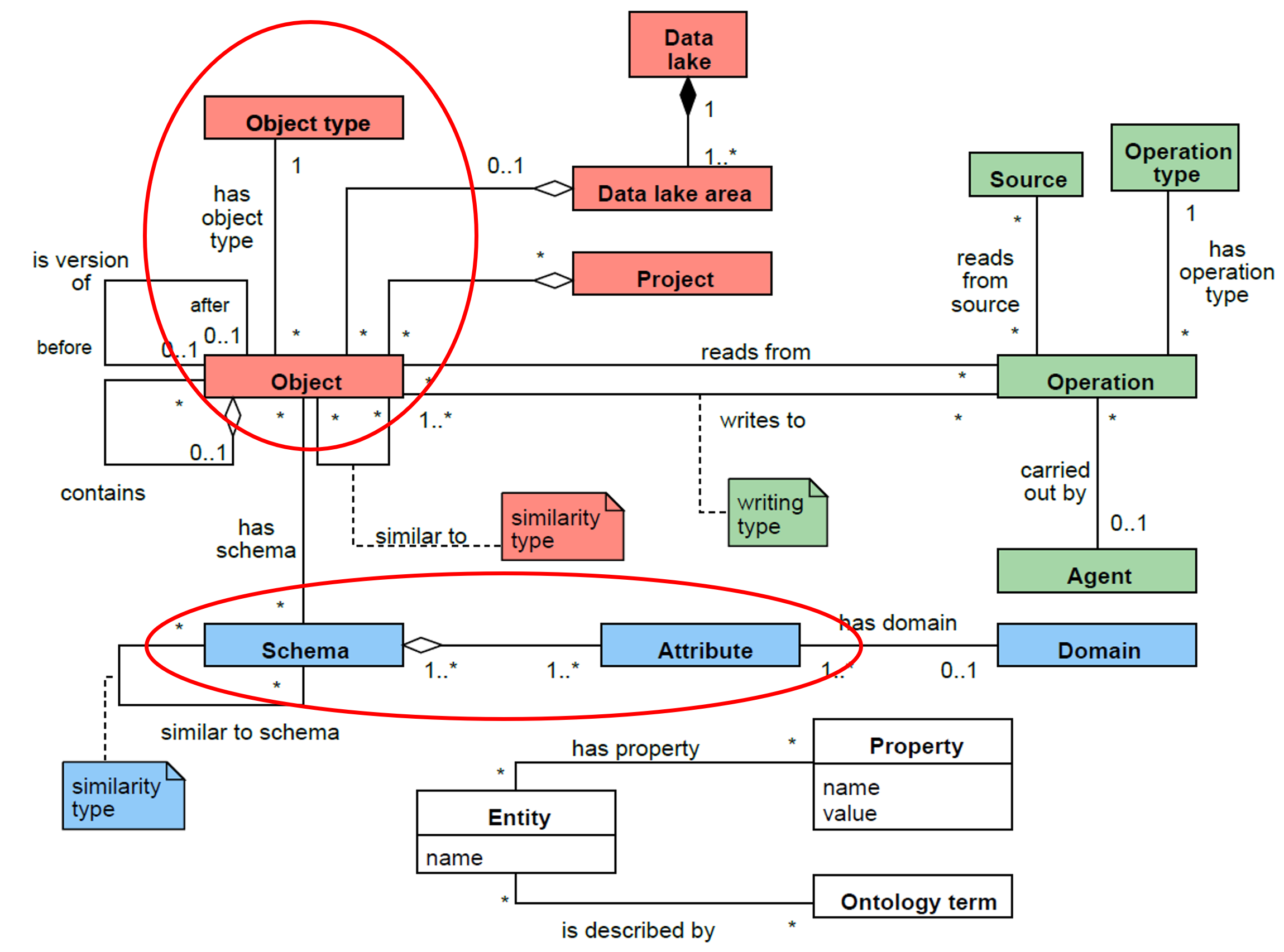

Another classification of metadata (Sawadogo et al. 2019)

Intra-object metadata

- Properties provide a general description of an object in the form of key-value pairs

- Summaries and previews provide an overview of the content or structure of an object

- Semantic metadata are annotations that help understand the meaning of data

Inter-object metadata

- Objects groupings organize objects into collections, each object being able to belong simultaneously to several collections

- Similarity links reflect the strength of the similarity between two objects

- Parenthood relationships reflect the fact that an object can be the result of joining several others

Global metadata

- Semantic resources, i.e., knowledge bases (ontologies, taxonomies, thesauri, dictionaries) used to generate other metadata and improve analyses

- Indexes, i.e., data structures that help find an object quickly

- Logs, used to track user interactions with the data lake

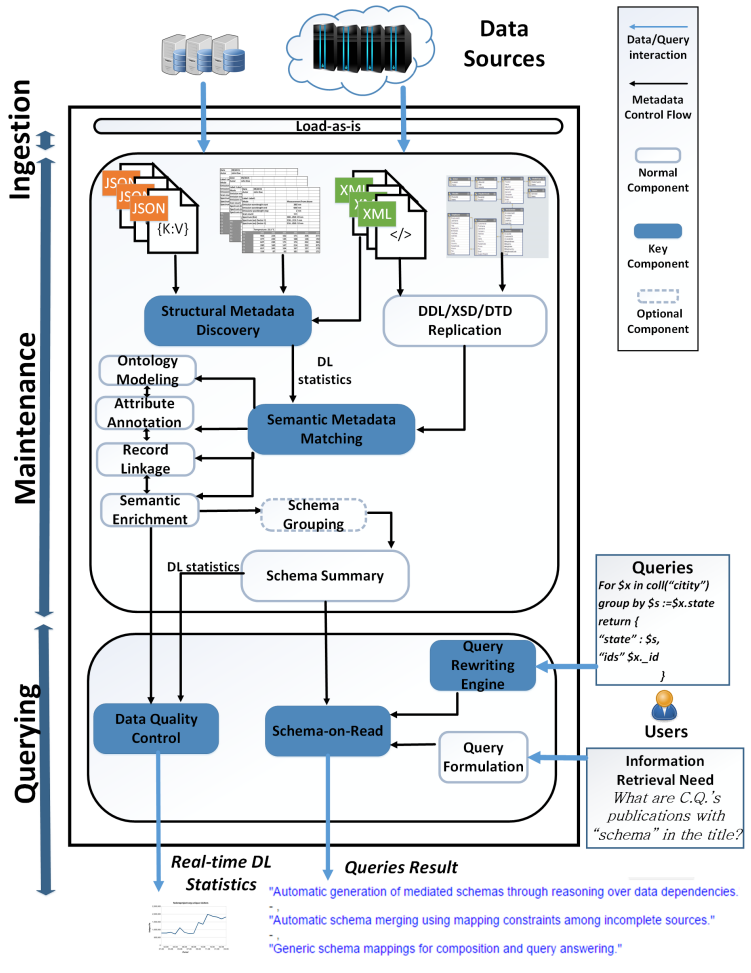

Capturing the metadata

Pull strategy

- The system actively collects new metadata

- Requires scheduling: when does the system activate itself?

- Event-based (CRUD)

- Time-based

- Requires wrappers: what does the system capture?

- Based on data type and/or application

- A comprehensive monitoring is practically unfeasible

Push strategy

- The system passively receives new metadata

- Requires an API layer

- Mandatory for operational metadata

Still one of the main issues in data platforms!

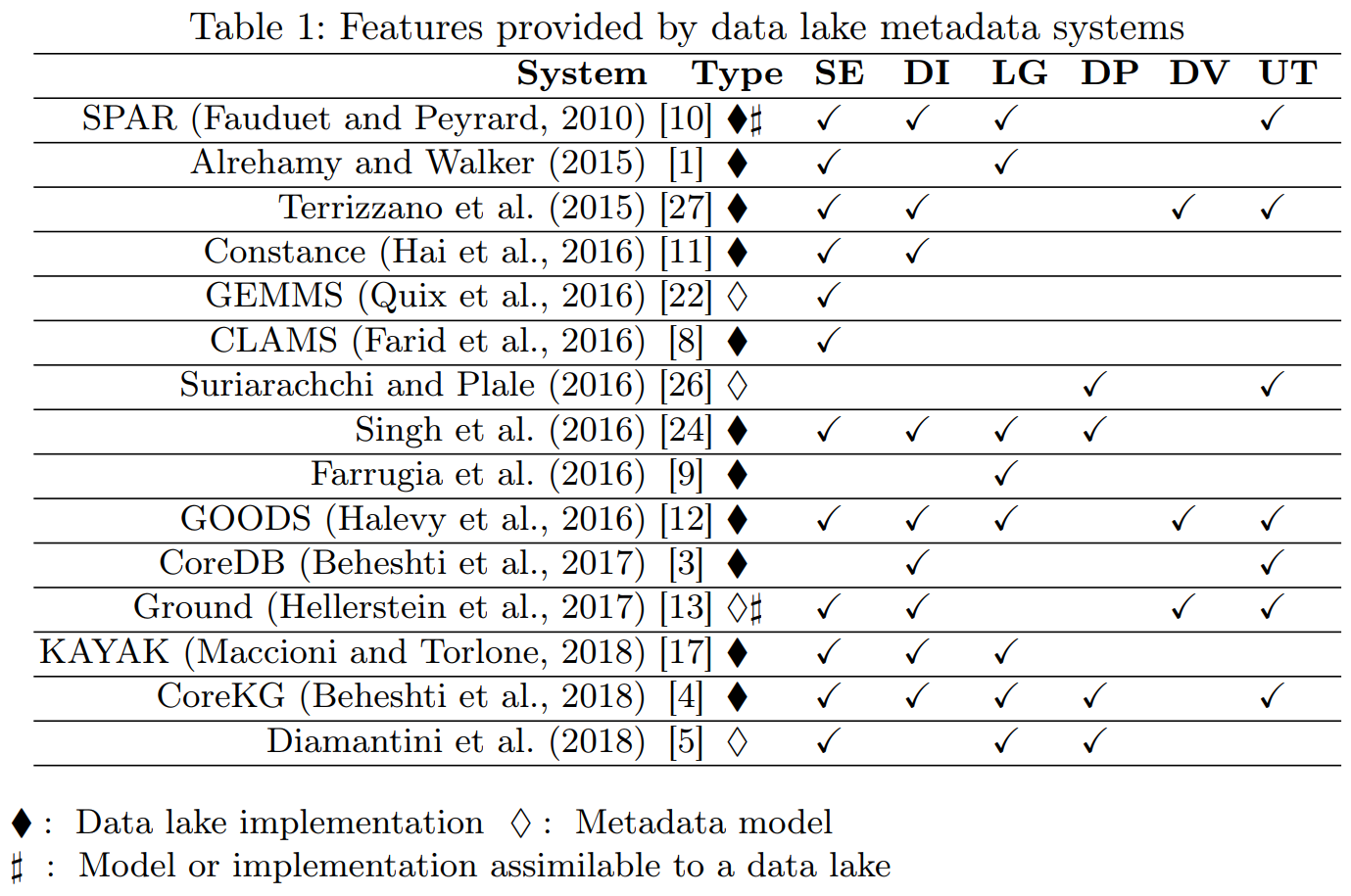

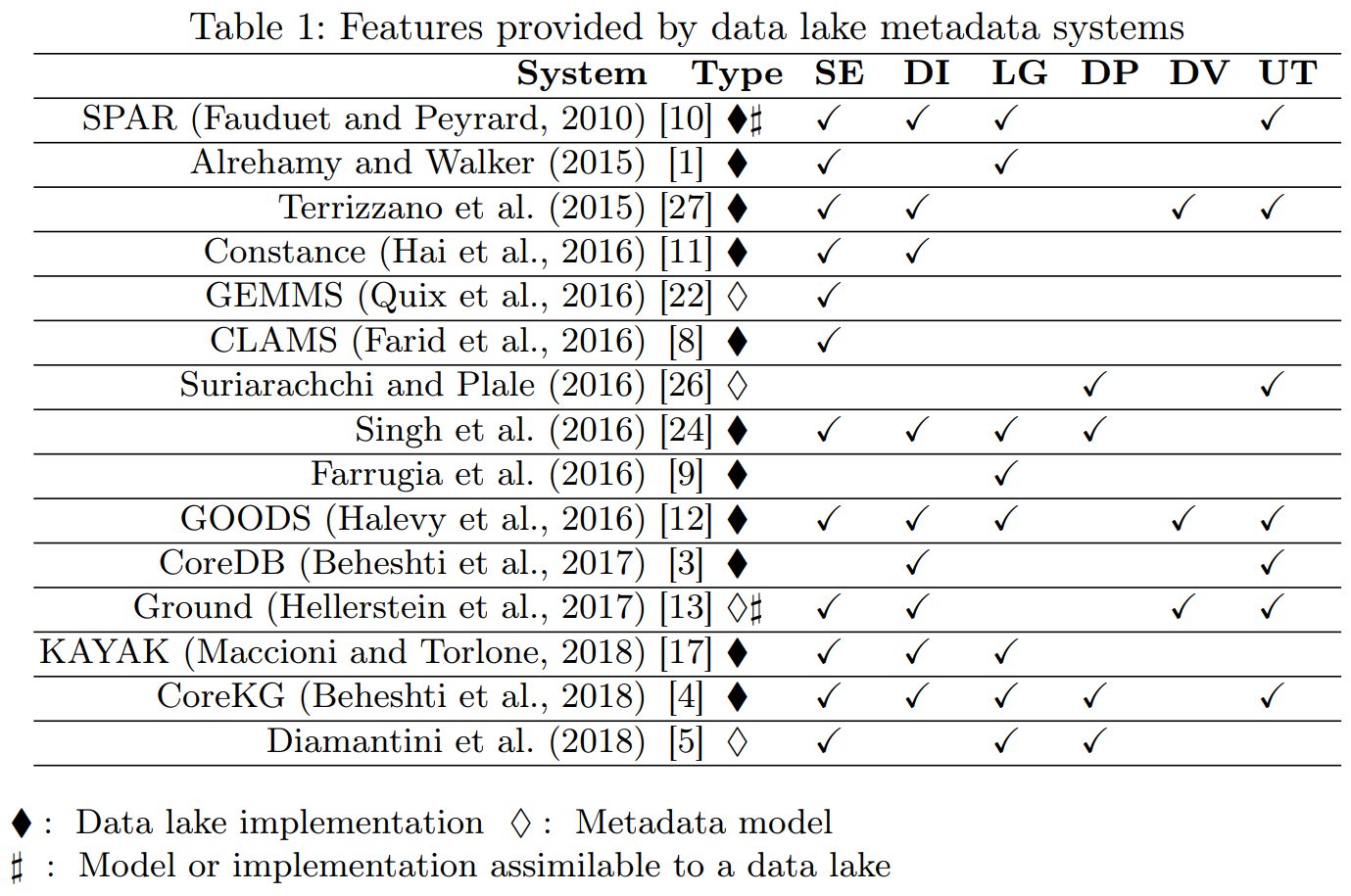

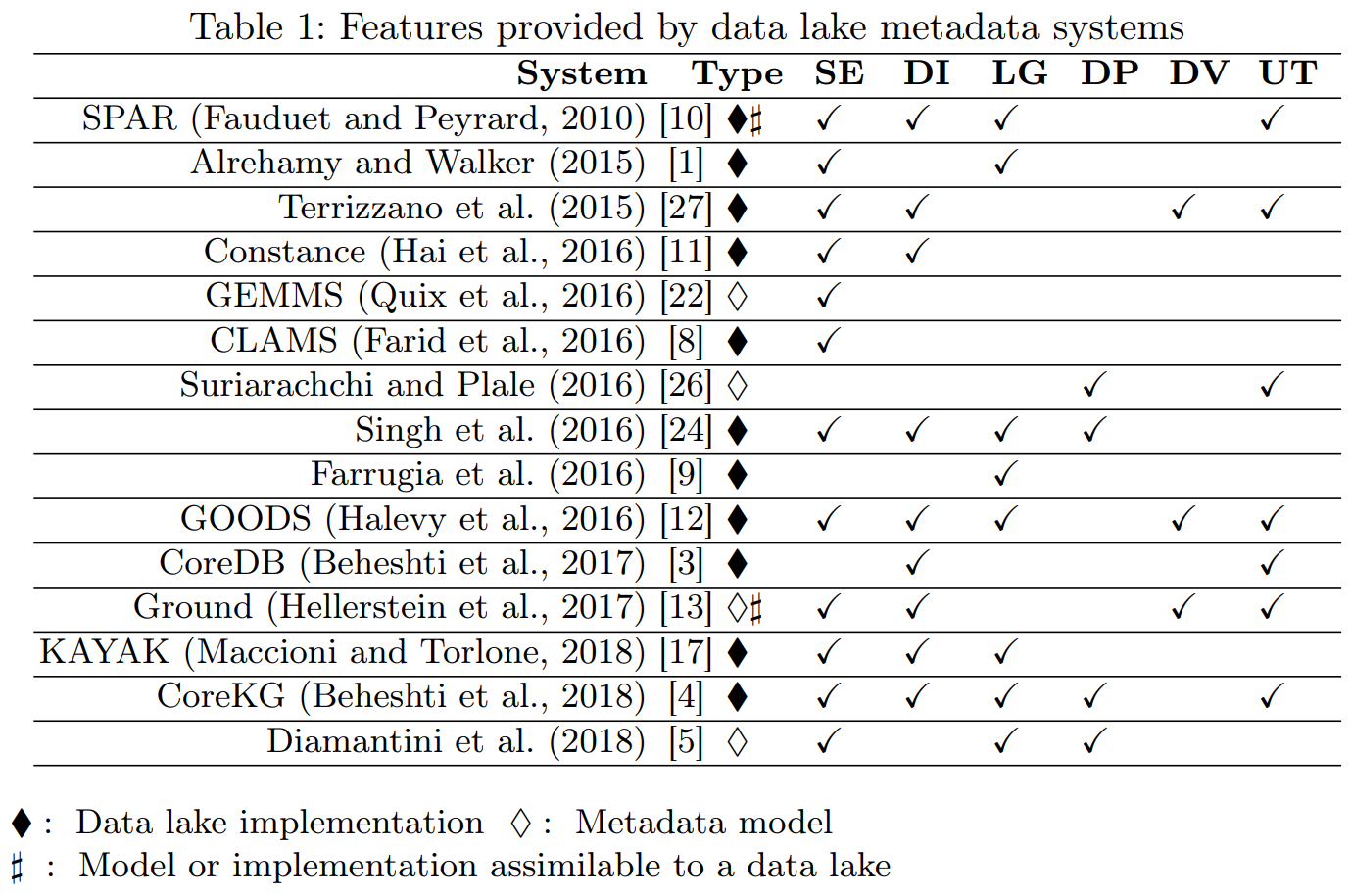

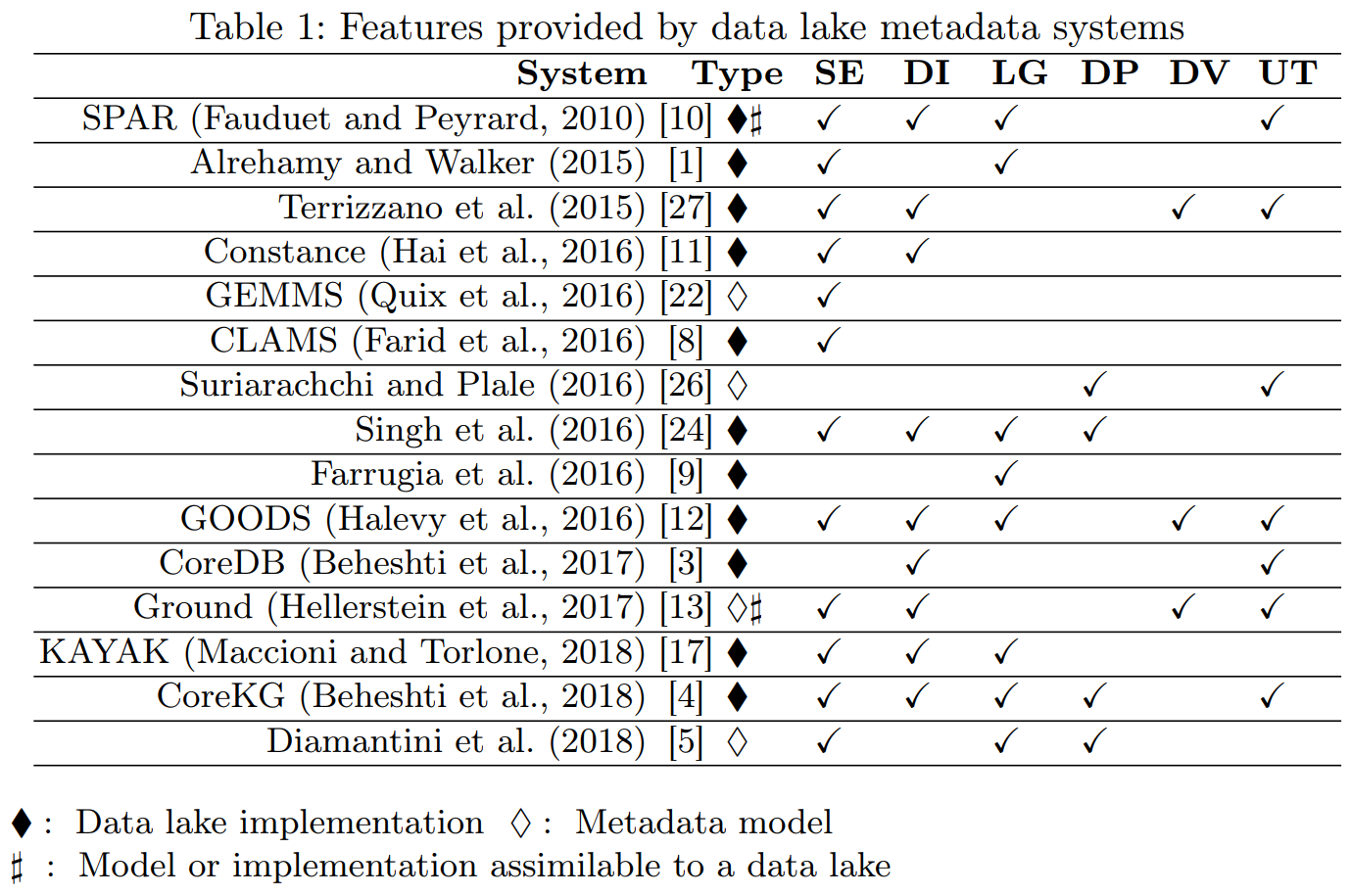

How should metadata be organized?

How should metadata be organized?

Semantic enrichment

- Add contextual descriptions (e.g., tags) for easier interpretation.

Data indexing

- Use structures to retrieve datasets by characteristics like keywords.

Link generation and conservation

- Detect similarities or maintain links between datasets.

Data polymorphism

- Store multiple data versions to avoid repeated pre-processing.

Data versioning

- Track data changes while preserving previous states.

Usage tracking

- Record user interactions with the data.

Constance: (Hai, Geisler, and Quix 2016)

- Few details given on metamodel and functionalities.

- No metadata collected on operations.

GEMMS: (Quix, Hai, and Vatov 2016)

- No discussion about the functionalities provided.

- No metadata collected on operations and agents.

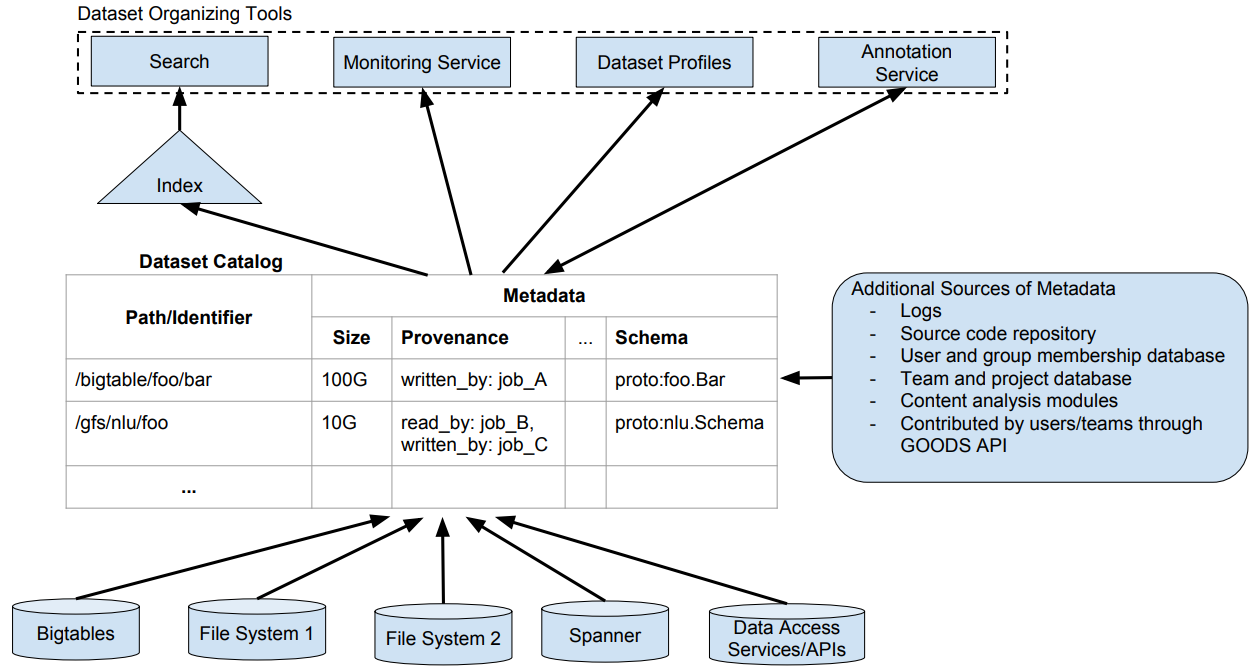

GOODS: (Halevy et al. 2016)

- Crawls Google’s storage systems to extract basic metadata on datasets and their relationship with other datasets.

- Performs metadata inference (e.g., determine the schema of a dataset, trace the provenance of data, or annotate data with their semantics).

- Strictly coupled with the Google platform.

- Mainly focuses on object description and searches.

- No formal description of the metamodel.

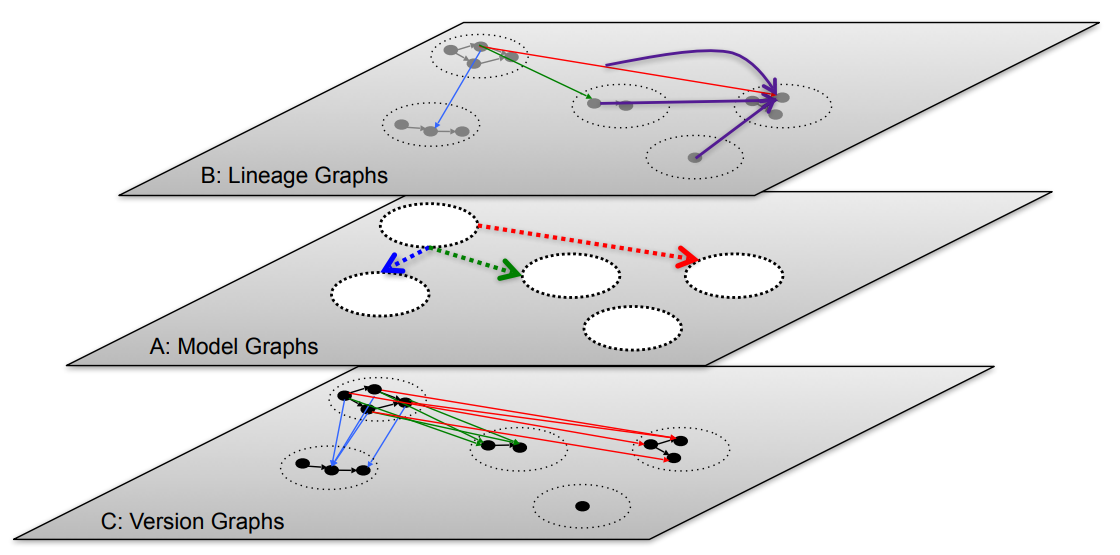

Ground: (Hellerstein et al. 2017)

- Version graphs represent data versions.

- Model graphs represent application metadata, i.e., how data are interpreted for use.

- Lineage graphs capture usage information.

- Not enough details given to clarify which metadata are actually handled.

- Functionalities are described at a high level.

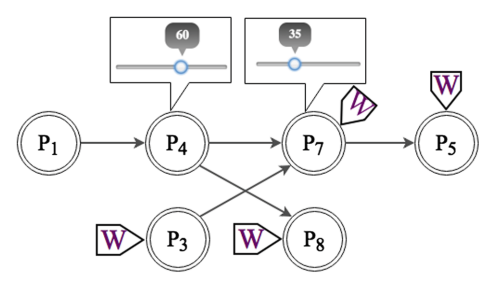

KAYAK: (Maccioni and Torlone 2018)

- Support users in creating and optimizing the data processing pipelines.

- Only goal-related metadata are collected.

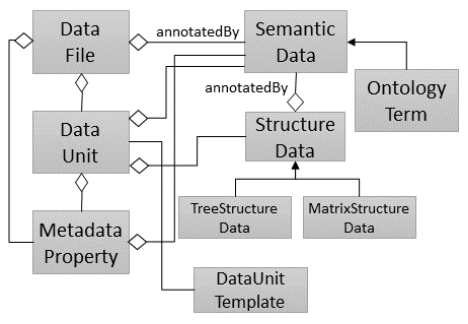

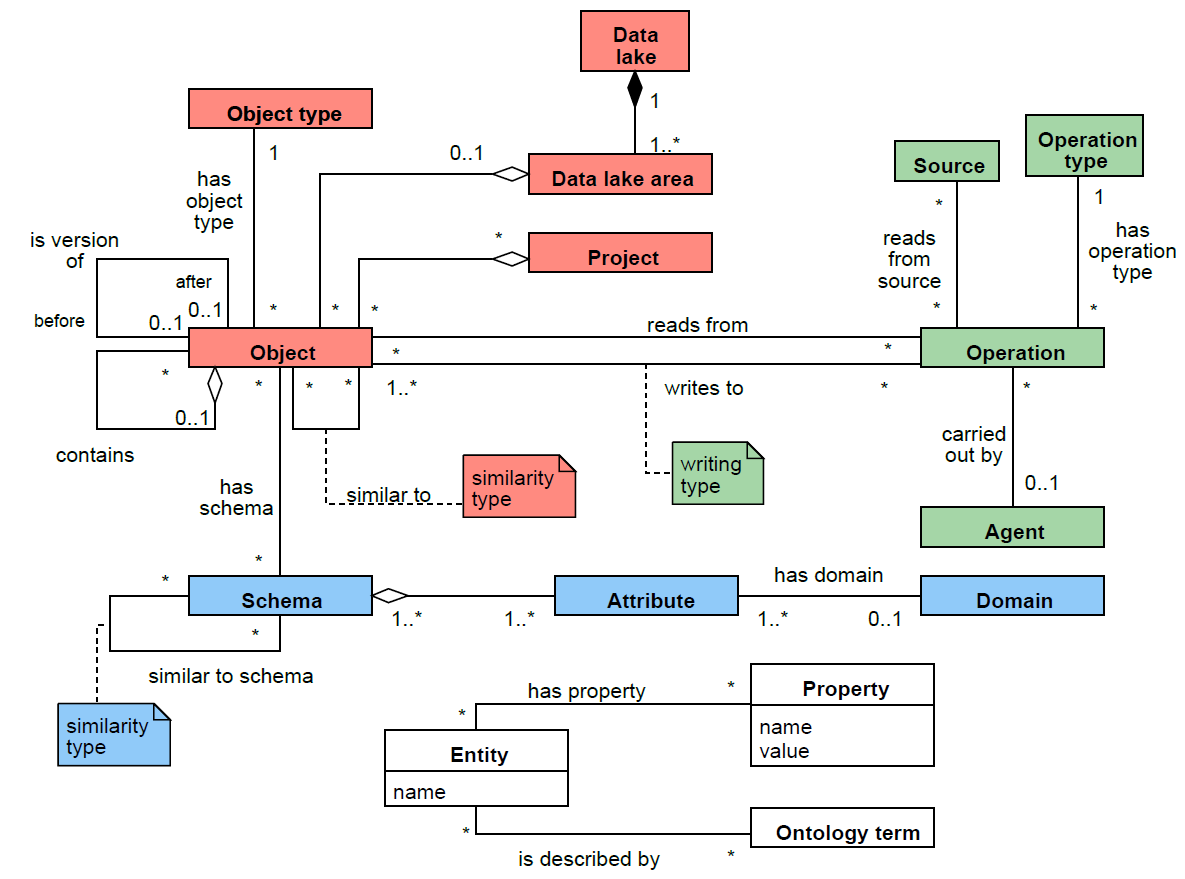

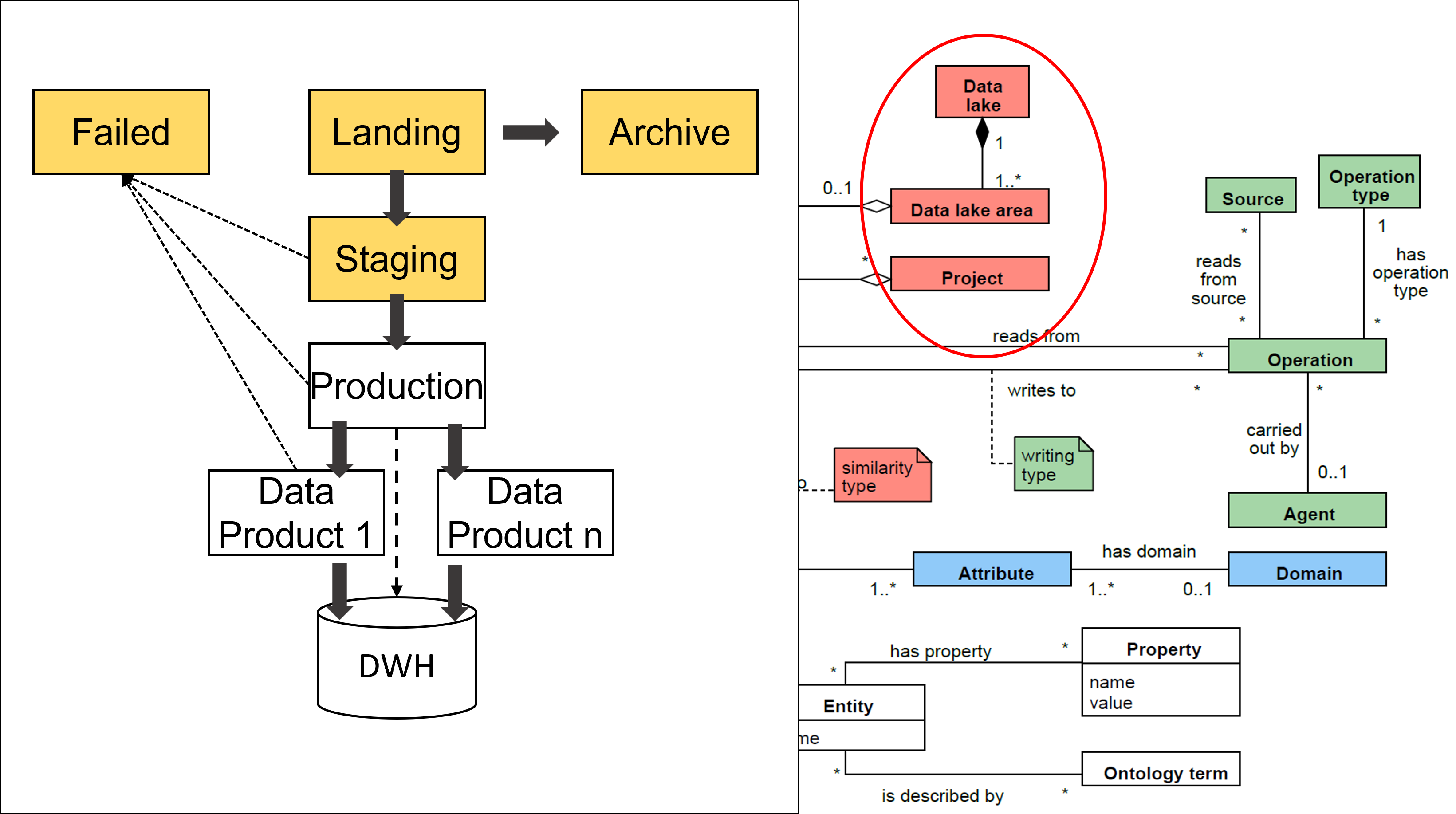

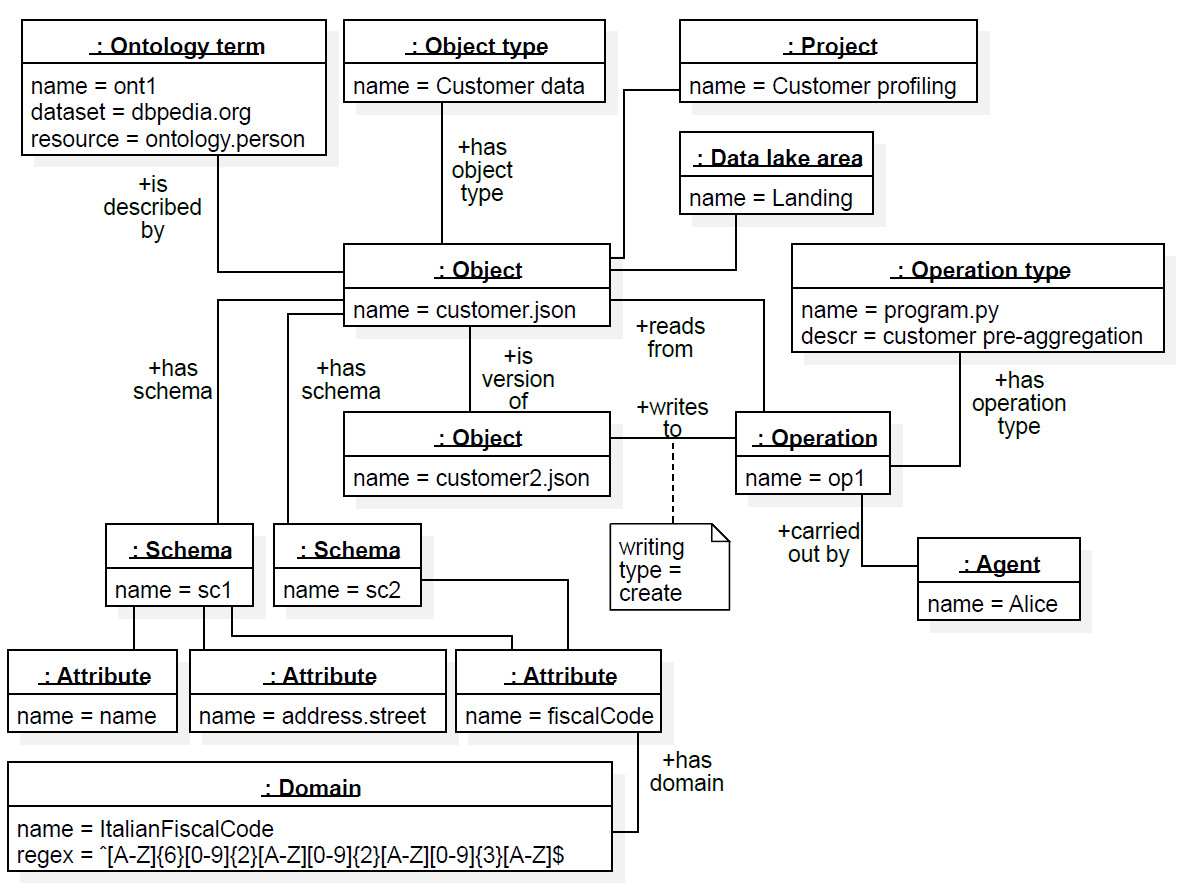

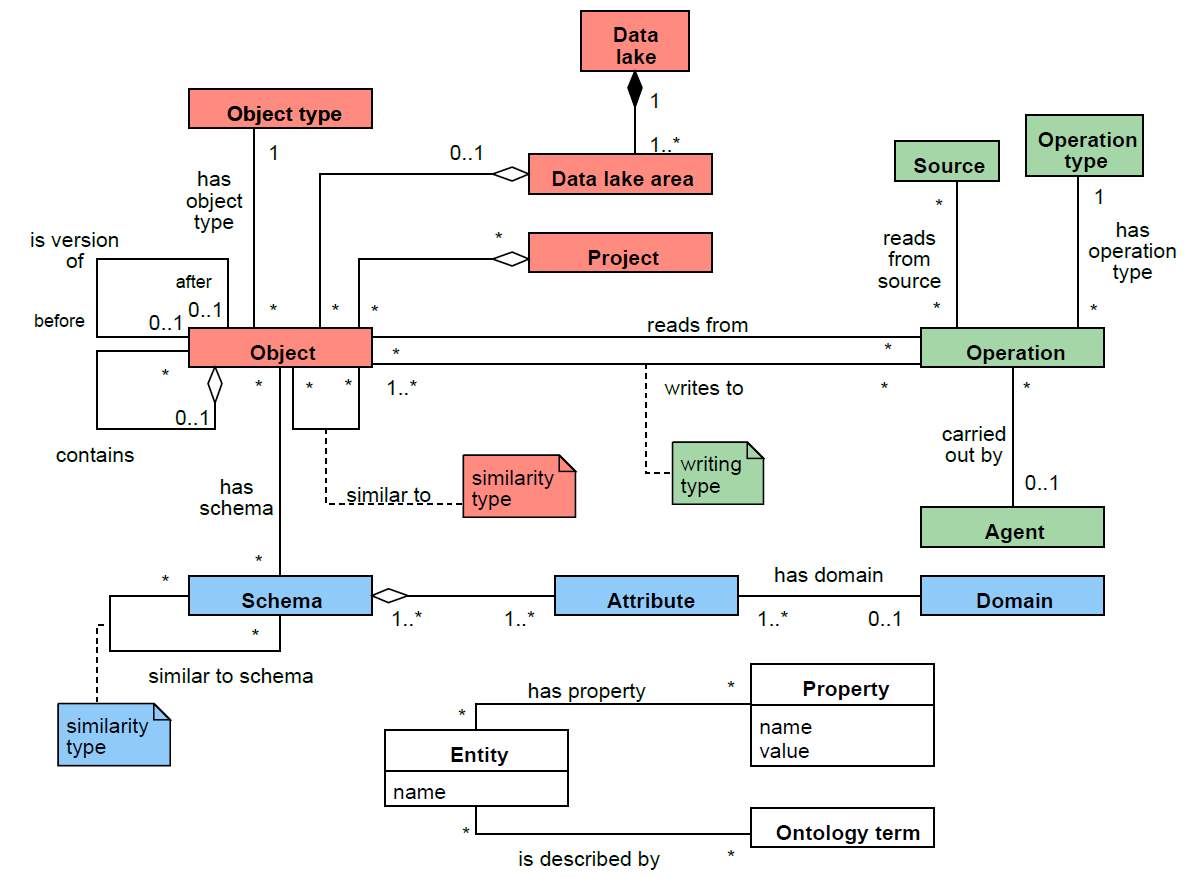

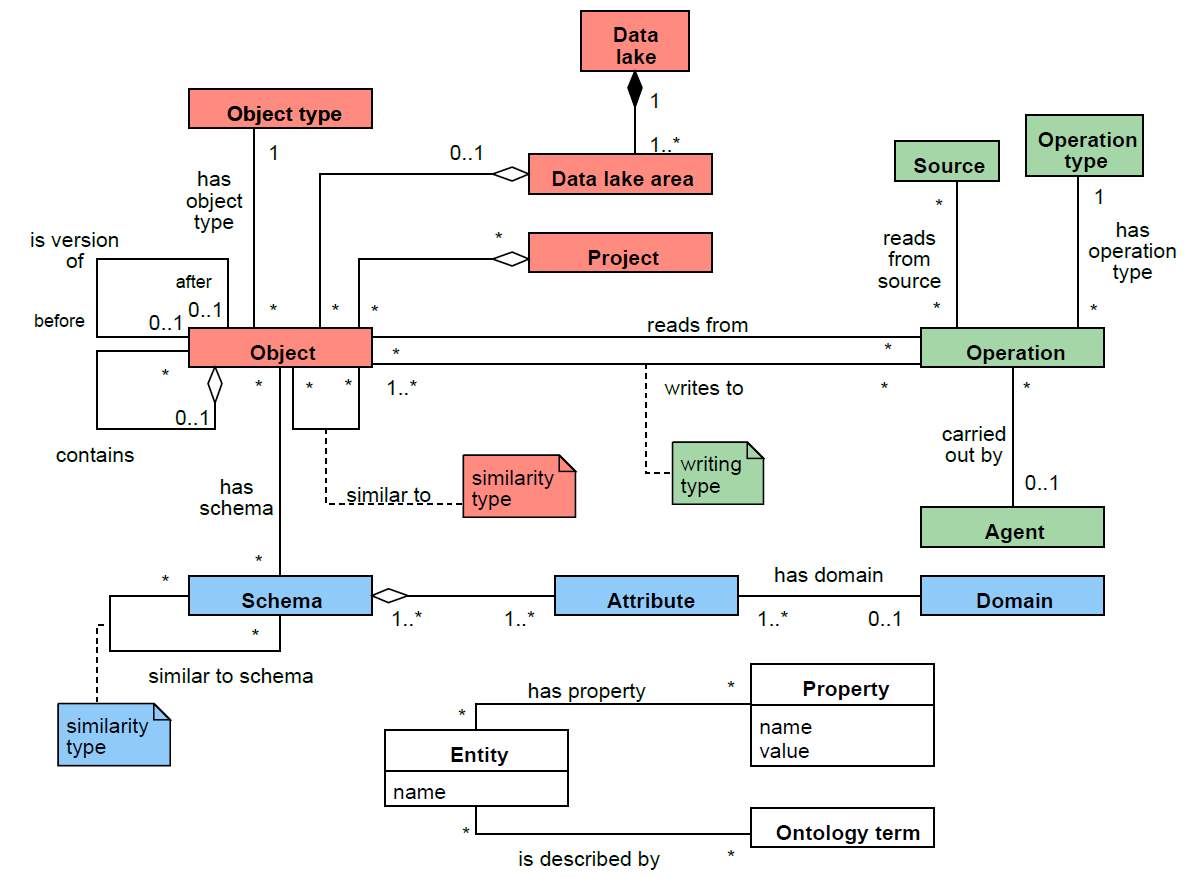

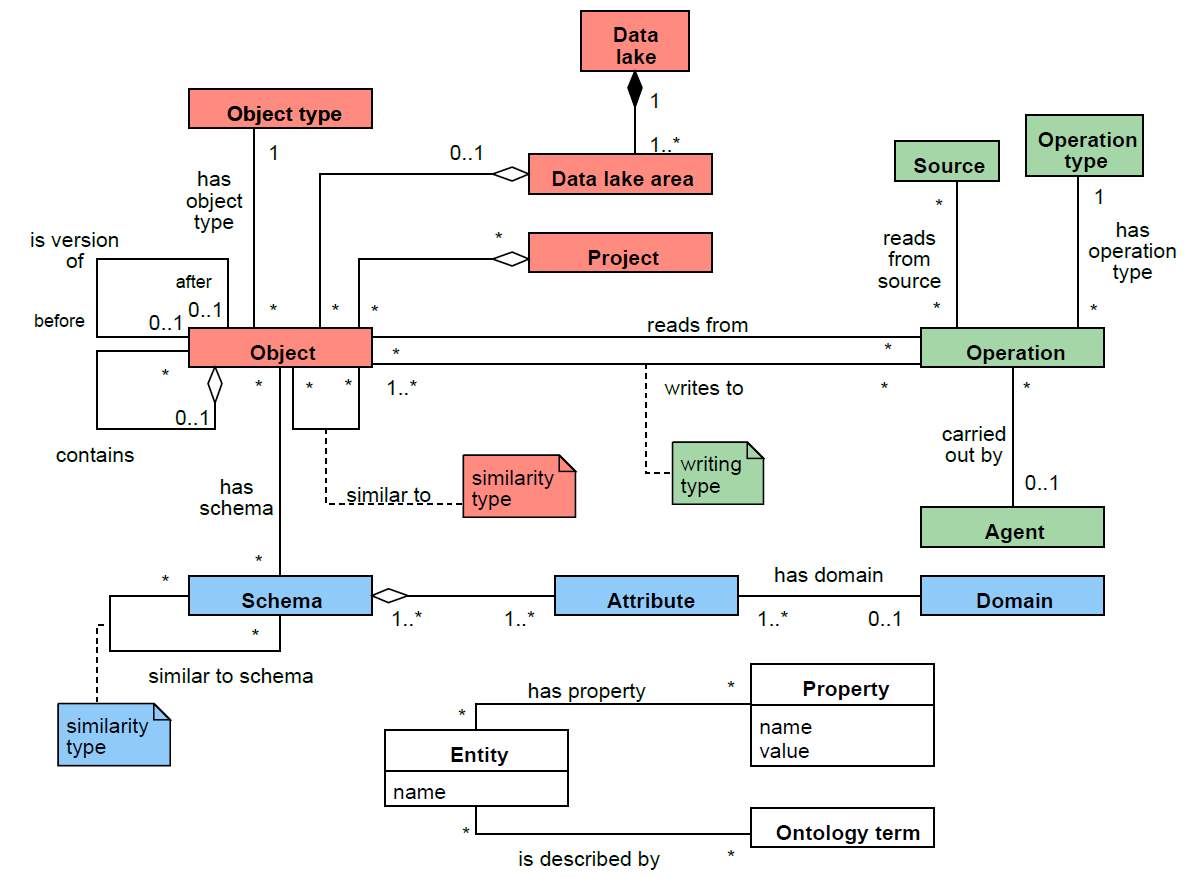

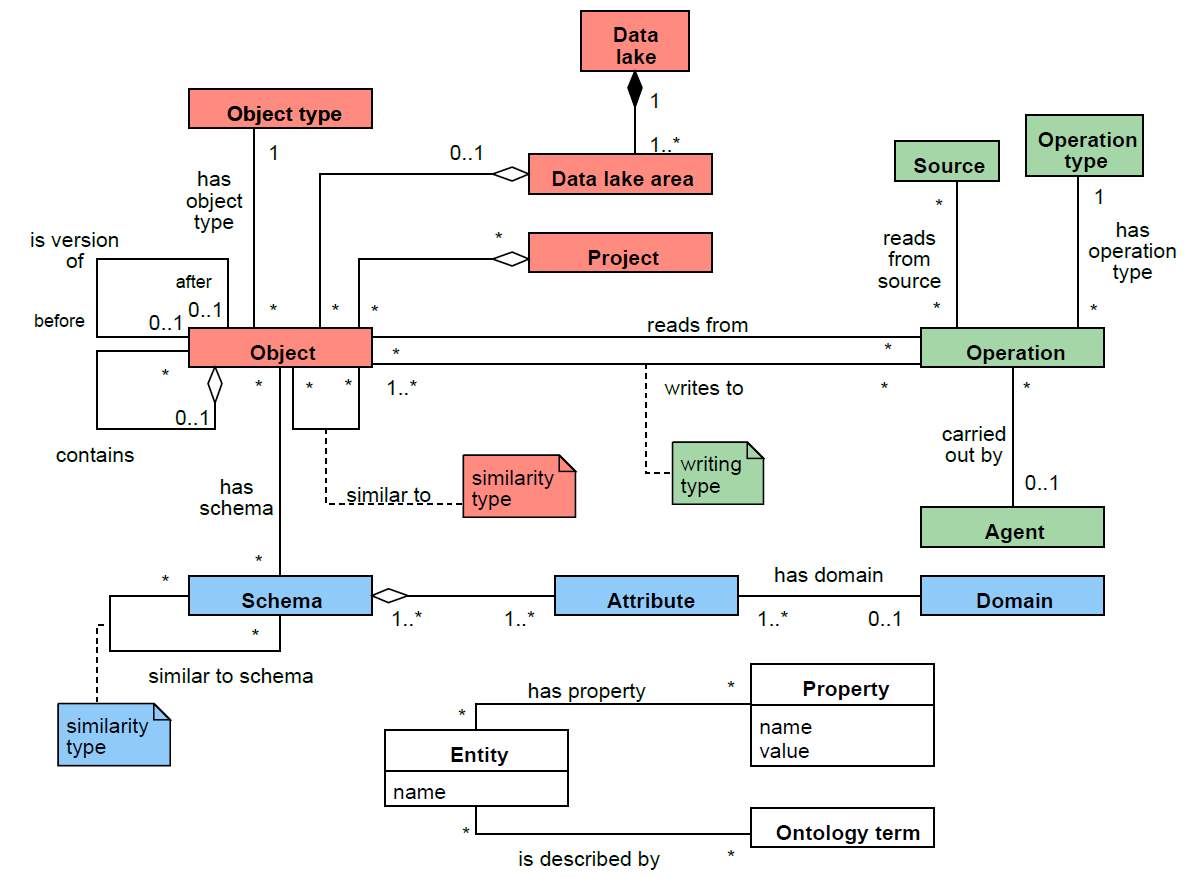

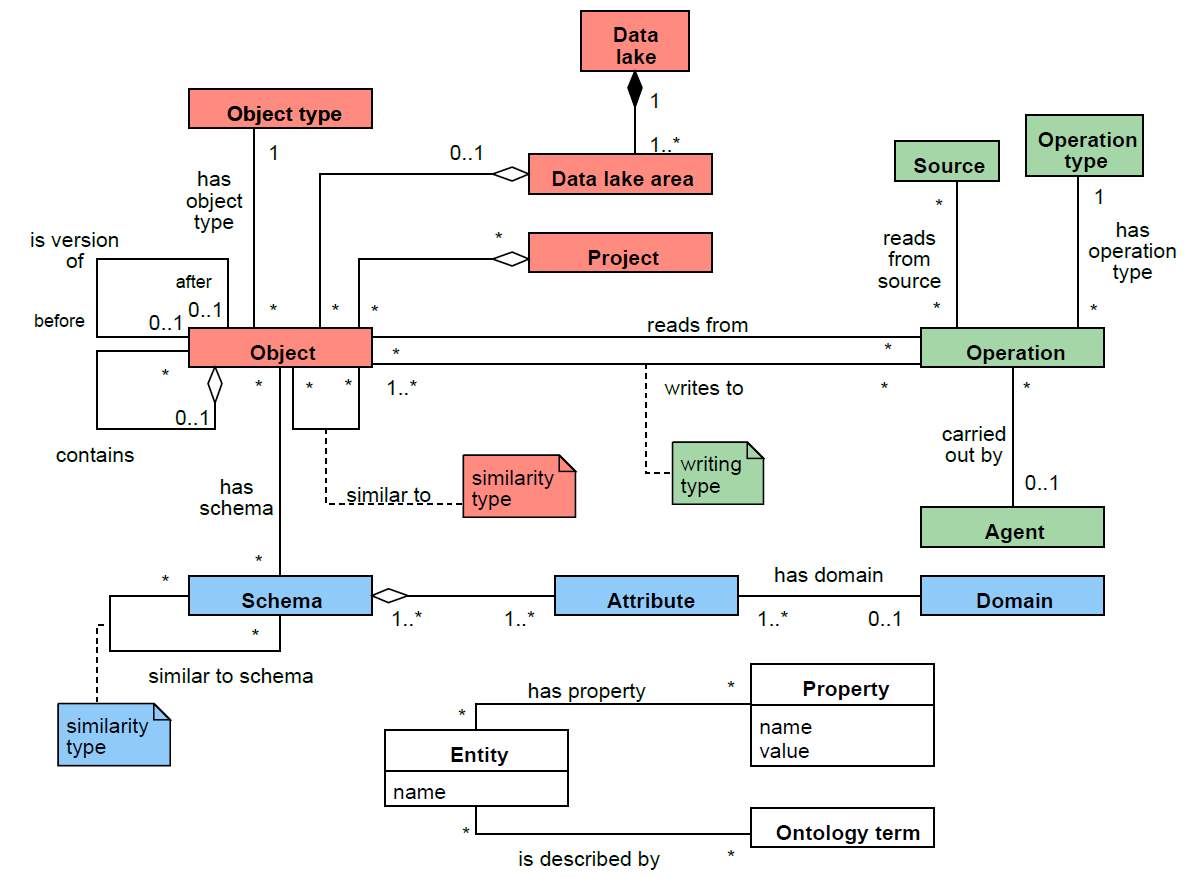

MOSES

Three areas:

- Technical (blue)

- Operational (green)

- Business (red)

- Not pre-defined

- Domain-independent

- Extensible

Tune the trade-off between the level of detail of the functionalities and the required computational effort

MOSES: (Francia et al. 2021)

| Functionality | Supported |

|---|---|

| Semantic enrichment | Yes |

| Data indexing | No |

| Link generation | Yes |

| Data polymorphism | Yes |

| Data versioning | Yes |

| Usage tracking | Yes |

How would you implement the meta-model?

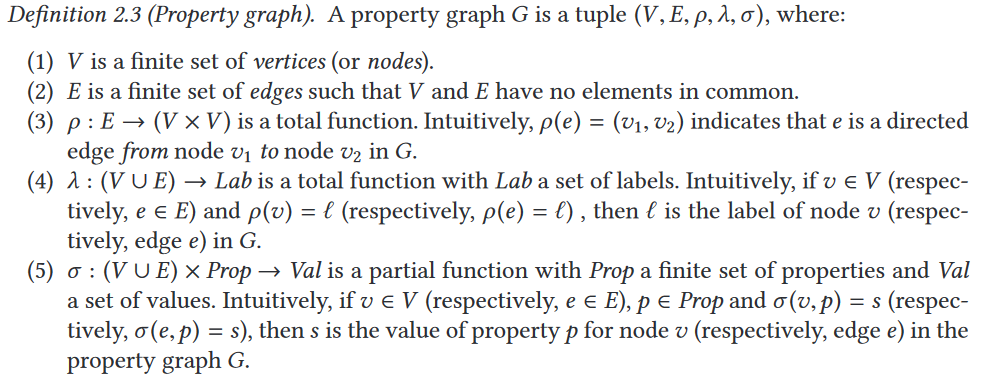

The Property Graph Data Model

Back in the database community

- Meant to be queried and processed

- THERE IS NO STANDARD!

R. Angles et al. Foundations of Modern Query Languages for Graph Databases

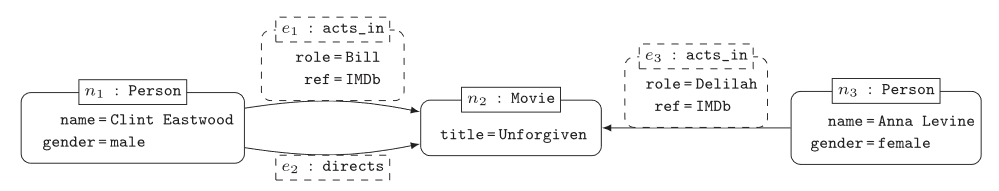

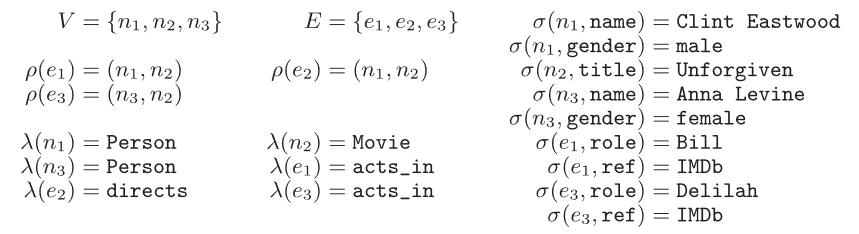

Example of Property Graph

Formal definition:

Traversal Navigation

Graph traversal: “the ability to rapidly traverse structures to an arbitrary depth (e.g., tree structures, cyclic structures) and with an arbitrary path description” [Marko Rodriguez]

Totally opposite to set theory (on which relational databases are based on)

- Sets of elements are operated by means of the relational algebra

Object search

Discoverability is a key requirement for data platforms

- Simple searches to let users locate “known” information

- Data exploration to let users uncover “unknown” information

- Common goal: identification and description of Objects

Two levels of querying

- Metadata level (most important)

- Data level (can be coupled with the first one)

Return all objects of a given project

Return small objects with a given name pattern in the landing area

MATCH (o:Object)-[]-(d:DataLakeArea)

WHERE d.name = "Landing" AND o.name LIKE "2021_%"AND o.size < 100000

RETURN oSchema-driven search: return objects that contain information referring to a given Domain

Provenance-driven search

MATCH (obj1:Object)-[:readsFrom]-(o:Operation)-[:writesTo]-(obj2:Object)

CREATE (obj1)-[:ancestorOf]->(obj2)Discover objects obtained from a given ancestor

Discover object(s) from which another has originated

Example: a ML team wants to use datasets that were publicized as canonical for certain domains, but they find these datasets being too “groomed” for ML

- Provenance links can be used to browse upstream and identify the less-groomed datasets that were used to derive the canonical datasets

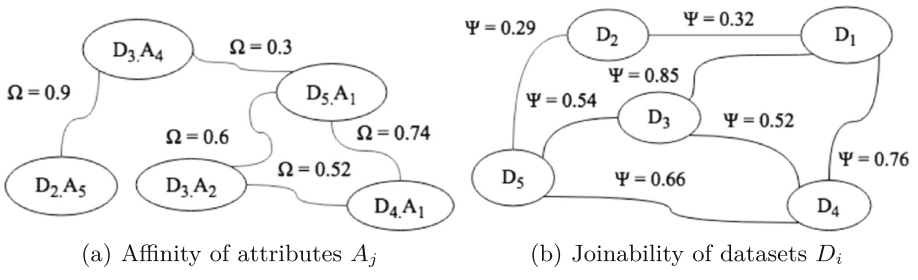

Similarity-driven search

Discover datasets to be merged in a certain query

Discover datasets to be joined in a certain query

Group similar objects and enrich the search results

- List the main objects from each group

- Restrict the search to the objects of a single group

Semantics-driven search

Search objects without having any knowledge of theirphysical or intensional properties, but simply exploitingtheir traceability to a certain semantic concept

Profiling

MATCH (o:Object)-[]-(:OntologyType {name:"Table"}),

(o)-[]-(s:Schema)-[]-(a:Attribute),

(o)-[r:similarTo]-(o2:Object),

(o)-[:ancestorOf]-(o3:Object),

(o4:Object)-[:ancestorOf]-(o)

RETURN o, s, a, r, o2, o3, o4- Shows an object’s properties, list the relationships with other objects in terms of similarity and provenance

- Compute a representation of the intensional features that mostly characterize a group of objects(see slides on schema heterogeneity)

References

Matteo Francia - Data Platforms and Artificial Intelligence - A.Y. 2025/26